Volusia County is blessed with an abundance and diversity of amazing water resources. Emerald blue springs, world-class beaches, productive coastal bays and lagoons, dozens of freshwater lakes and the unique St. Johns “River of Lakes” are all integral to the beauty and quality of life in our subtropical paradise. As an environmental scientist who was born, raised and educated in Florida, I feel incredibly fortunate to be working with so many members of our community who are dedicated to the protection of what Dr. Robert Sitler, my colleague at Stetson University, calls “Aquatic Gems.”

The Aquatic Gems are not only of great ecological importance but also are key drivers within the local economy. The aquamarine waters of our Atlantic beaches are undoubtedly the most famous attraction for the millions of visitors who come to Volusia County each year. Over in West Volusia, several hundred thousand people line up annually to see the amazing spectacle of over 700 wintering manatees gathered in the warm waters of Volusia Blue Spring. The more ambitious Volusia County explorer has the opportunity to see the incredible bioluminescence of the summer mullet runs in the Indian River Lagoon or the acrobatic congregations of swallow-tailed kites at Lake Woodruff National Wildlife Refuge.

There is, of course, not enough space in a short essay to make note of all the unique places where our local waters support abundant wildlife, enriching the lives of both residents and tourists alike. But I do think that one thing that unites most of us, regardless of our differences on the other issues of our times, is a deeply felt commitment to steward the health of these waters for ourselves, our children, our grandchildren and, indeed, those who are not yet born.

However, I often warn my students at Stetson that one of the occupational hazards that comes with being an environmental scientist is an obligation to maintain objective awareness of how our environment is being impacted by human activities. Despite all of the best intentions, a clear-headed assessment of our local waters provides unfortunate evidence that we simply have not done – and are not doing – enough.

Perhaps most dramatically, a series of harmful algal blooms in the Indian River Lagoon, caused by increasingly poor water quality, have destroyed large areas of critical seagrass habitat and negatively impacted our coastal fisheries. In maybe the saddest thing I’ve ever seen in my professional career, the loss of seagrass has finally reached a tipping point and, since early 2021, brought on a lethal starvation crisis among our coastal manatee population.

We can, and must, do better than this. This call to action, though, seems to beg two important questions: 1) What exactly are we doing wrong? and 2) How can we do better?

The first question is easiest to answer, at least from the vantage point of objective science. It is very well understood that historical and ongoing carelessness with nutrient contaminants, primarily nitrogen and phosphorus, has overfertilized many of our waterways, resulting in harmful algal blooms. Well-known sources such as septic tanks, fertilizer runoff from yards and farms and, in some places, discharges from old wastewater treatment plants all contribute to the problem.

To their credit, our local leaders in Volusia County have attempted to do better. For example, our County Council passed a restrictive fertilizer ordinance in 2014 with the express intent of reducing nutrient runoff into our Aquatic Gems. Several local governments are also moving forward with septic to sewer conversions in certain areas of the County, which is a proven strategy for improving local water quality in sensitive locations. However, I’ll be frank in saying that our current efforts, while undoubtedly well-meaning, are not proving to be enough.

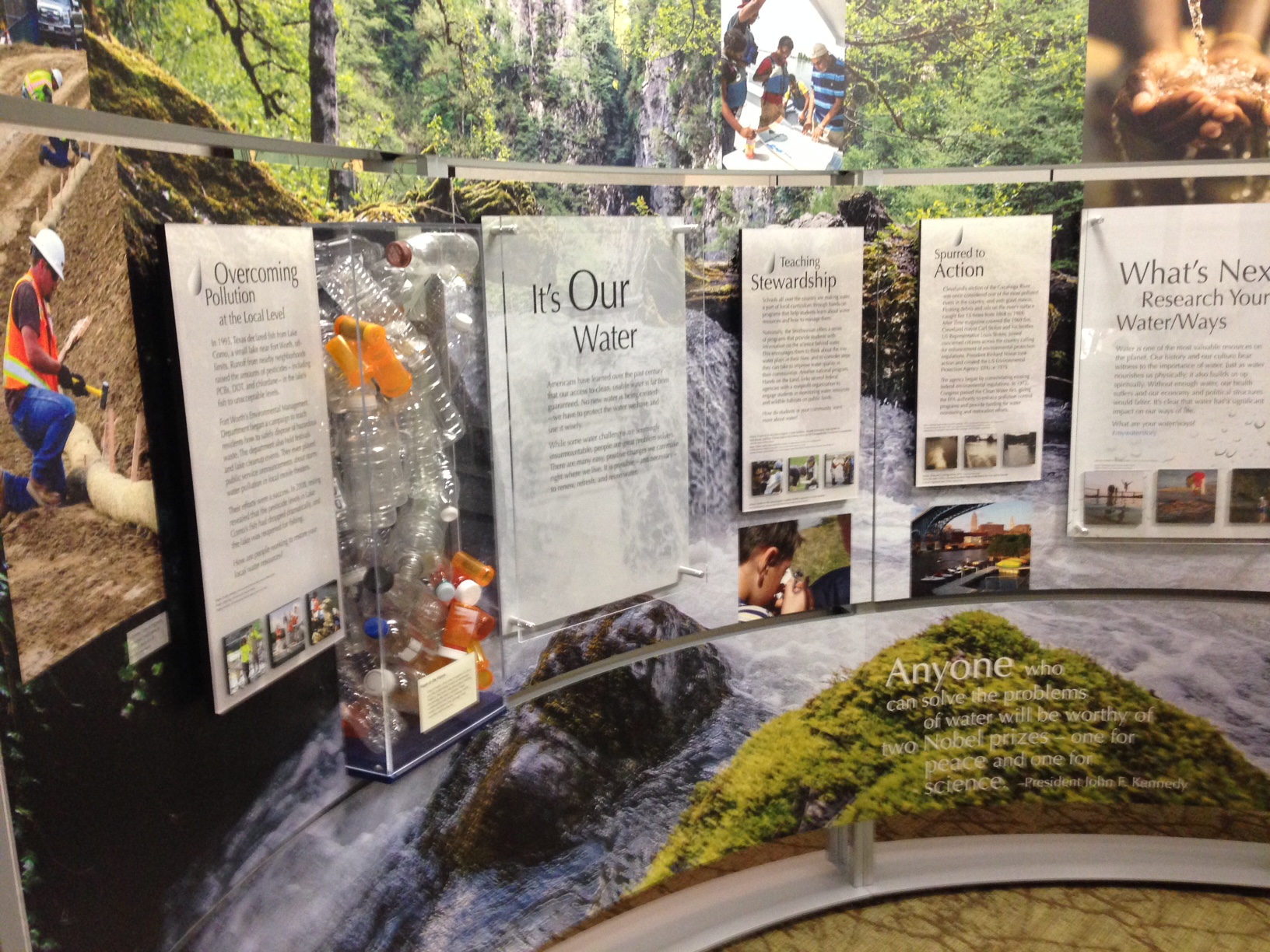

One of the most promising set of “new” technologies for doing more to improve our waters goes by the fancy moniker of “green infrastructure.” I use the scare quotes around “new” to indicate that much of what we call green infrastructure isn’t really new at all but instead represents more thoughtful ways of utilizing our native soils, wetlands and plants for storage and filtration of water from the built environment. Living shorelines, rain gardens and stormwater wetlands are just a few of the green infrastructure practices that can provide restorative benefits throughout our communities.

Some examples of such green infrastructure practices put into action can be seen in demonstration projects at Stetson’s Institute for Water and Environmental Resilience in DeLand, the Marine Discovery Center in New Smyrna Beach and the Riverside Conservancy in Edgewater. But we need to move rapidly from a place where green infrastructure is seen as a novelty being put into action by a few early adopters and into a standard – even required – development practice in support of restoring our waters. Similarly, we need to evolve away from the unfortunate “business-as-usual” development that too often involves over-paving, over-fertilizing and over-watering within our built landscapes.

I’ll conclude with more optimism that the water resource solutions we develop here in Volusia County, and other areas of central Florida, will be highly transferable to other areas of the country and the world. Clean technology solutions, such as green infrastructure, promise to be one of the biggest growth industries in the 21st century. I am confident that our local community is positioned to be a global leader in these industries through the talents of our citizens, as well as the richness and complexity of our natural laboratories, i.e., the Aquatic Gems. I have faith that, together, we can and will make this future happen.