Fort Mose: America’s First Free Black Town

In 1687, a group of eight men, two women and a child traveled by dugout seeking freedom from enslavement in a Carolina colony. They found it in St. Augustine.

Four years later, the Spanish King Carlos II issued the first official crown position on runaway enslaved people that made their way to Spanish Florida. In the royal cedula, called ‘Cedula Real de Gracia de 1693’, the king granted “liberty to all … so that by their example and by my liberality others will do the same.”

The grant of freedom, however, was not without a price. The former enslaved were required to swear an oath to the Spanish crown and convert to Catholicism. While the Spanish may have been motivated by “liberality” in recognizing the essential humanity and rights of formerly enslaved people, the policy of granting runaway enslaved people their freedom was also a political and military necessity for a nation competing for colonial lands in the New World.

Initially, former enslaved people who found refuge in St. Augustine lived in the city and were put to work. The eight men in that first group became ironsmiths and waged laborers building the new stone fort that would become the Castillo do San Marcos. But because of Florida’s strategic significance to Spain’s Caribbean colonies – and the growing influx of runaway enslaved people to Spanish Florida – the role of the former enslaved took on a greater significance.

According to an article by Jane Landers in the American Historical Review in February 1990, “Spaniards depended upon Africans to be their laborers and to supplement their defenses. Black laborers and artisans helped establish St. Augustine, the first successful Spanish settlement in Florida, and a black and mulatto militia was established there as early as 1683.”

For their part, the now freed enslaved people understood their expected role in Spanish Florida. In a declaration to the king, they vowed to be “the most cruel enemies of the English” and to fight to “the last drop of blood in defense of the Great Crown of Spain and the Holy Faith,” according to Landers’ article.

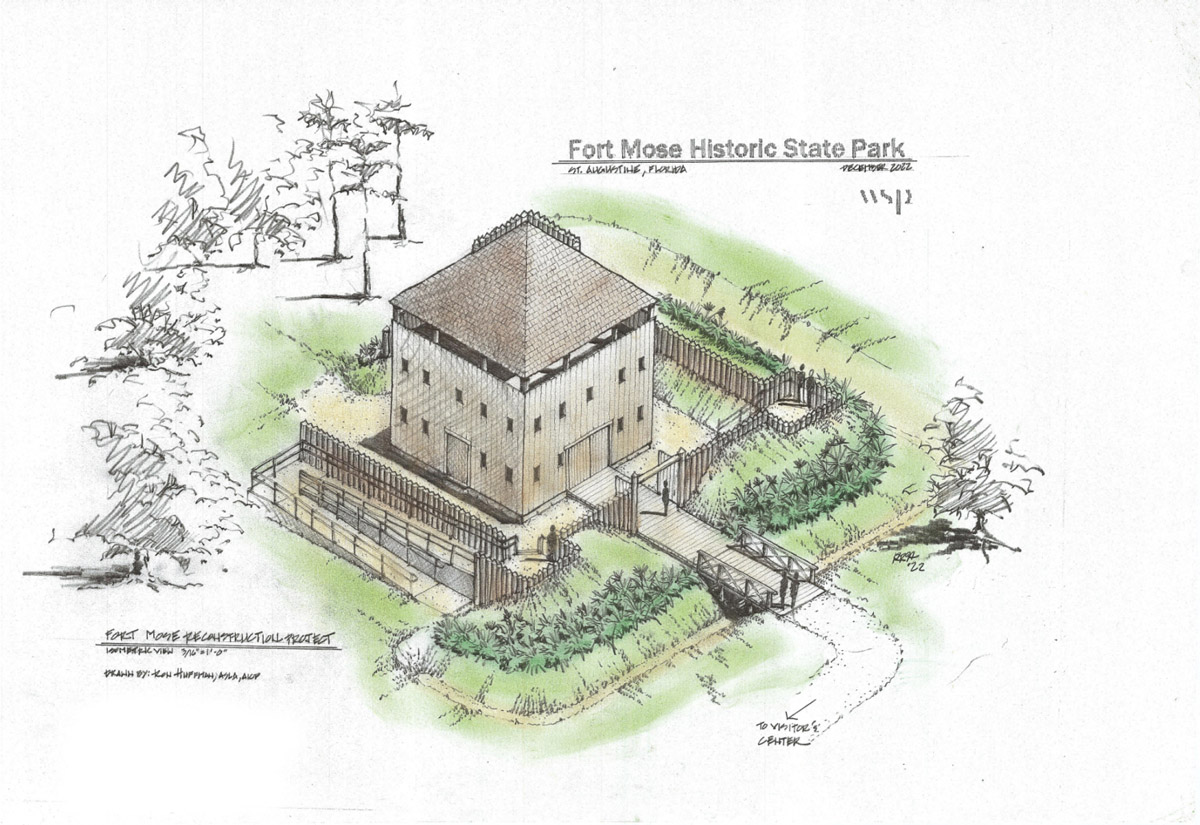

As British colonization in North America grew and tensions between England and Spain over colonial ambitions increased, Spanish officials in Florida looked for ways to protect their settlements. In 1737, Manuel de Montiano became governor in St. Augustine; the next year he established a new town two miles north of the city called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose. The name, according to Landers, was a composite of an existing Native American place name, Mose, with the addition of language commemorating its establishment by the Spanish Crown, Gracia Real, and the name of the town’s patron saint, St. Teresa of Aviles.

Thus was born Fort Mose, the first legally sanctioned free Black community within the present boundaries of the United States.

The new town was established as a buffer against foreign encroachment, specifically the British to the north. According to later British reports, the fort was constructed of wood “four square with a flanker at each corner, banked with earth, having a ditch without on all sides lined round with prickly royal and had a well and housing within a lookout.”

Fort Mose was soon put to the test in 1740 when tensions among Europe’s Great Powers erupted into conflict.

With Britain and Spain at war, a force under British Gov. James Oglethorpe raided Florida and threatened St. Augustine – the battle of Bloody Mose. During the British attack, Fort Mose was captured, but all its inhabitants reached the safety of the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, as Governor Montiano ordered its evacuation prior to the battle. Oglethorpe’s forces were eventually defeated, but Fort Mose was badly damaged in the battle and was abandoned for a dozen years.

In 1752, the fort was rebuilt and remained an active part of the defense of St. Augustine until 1763, when it was abandoned at the end of the Seven Years’ War between the Great Powers of Europe. In North America, it was known as the French and Indian War and was part of the struggle between France and Great Britain for colonial ascendency in the New World.

The reconstructed fort became part of a defensive perimeter built by the Spanish that extended from Mose southwest to a stockade on the banks of the San Sebastian River. The second fort was a three-sided structure equipped with two 4-pound canons and six swivel guns, according to a 1993 article in The Florida Anthropologist by Bruce Piatek, a former director of the Florida Agricultural Museum in Flagler County, and Carl D. Halbirt entitled “The Stratigraphy of the Mose Line: St. Augustine’s Last Line of Defense.” The unprotected side of the fort faced what is now called Robinson Creek.

The inhabitants of Fort Mose, along with the Spanish settlers in Florida, fled to Cuba, with many settling in the province of Matanzas. The fort was refurbished by the British in 1784. It was destroyed and abandoned in 1812 after a failed attempt by a group of Americans who called themselves the Florida Patriots to seize the peninsula for the United States.

For more than 150 years, Fort Mose disappeared from memory until the site was rediscovered through the efforts of legislators, scientists and historians, according to Kathleen Deagan and Darcie MacMahon in their book “Fort Mose: Colonial America’s Black Fortress of Freedom.”

Deagan, with the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida, led the research project and uncovered a wide range of detailed information about the fort.

Landers conducted the primary historical research and was also involved in the work uncovering the lost fort, using old documents and maps in the colonial archives of Spain, Florida, Cuba and South Carolina.

But historical maps were not enough to determine where the long-vanished fort had been, according to Deagan and MacMahon.

“Historical documents were combined with space age technology to determine the location of Fort Mose,” they said.

The location of the first fort now lies at the bottom of a salt marsh, but thermal imaging was used to discover the small square structure of the fort. The second fort was found using aerial photographs, old maps and archaeological remains, Deagan and MacMahon said. The discovery of the location allowed for an archaeological excavation of the site, which has uncovered a wealth of data about the fort and its inhabitants.